In the previous post, I covered the protobuf (schema definition) part of the solution. This post will focus on how we create or patch BigQuery tables without interrupting the real-time ingestion.

2 BigQuery

BigQuery is Google’s serverless data warehouse, and it is awesome (and I’ve experience from Hive, Presto, SparkSQL, Redshift, Microsoft PDW, …). It is a scalable data solution that helps companies store and query their data or apply machine learning models.

2.1 Schemas and evolution

BigQuery natively supports schema modifications such as adding columns to a schema definition and relaxing a column’s mode from REQUIRED to NULLABLE (but protobuf version 3 defines all fields as optional, i.e. nullable). It is also valid to create a table without defining an initial schema and to add a schema definition to the table at a later time.

All other schema modifications are unsupported and require manual workarounds, for example changing a column’s name, data type or mode or if you want to delete a column.

Hence, the schema evolution I refer to is basically adding fields, but that is also 90% of our cases. If we want to make breaking changes (according to protobuf rules) we basically make a new table with a new major version. If it is a protobuf non-breaking change (renaming or changing some data types), then we basically make a temporary table with the new schema, backfill it and then overwrite the old table with the new and update the dataflow pipeline with the new schema.

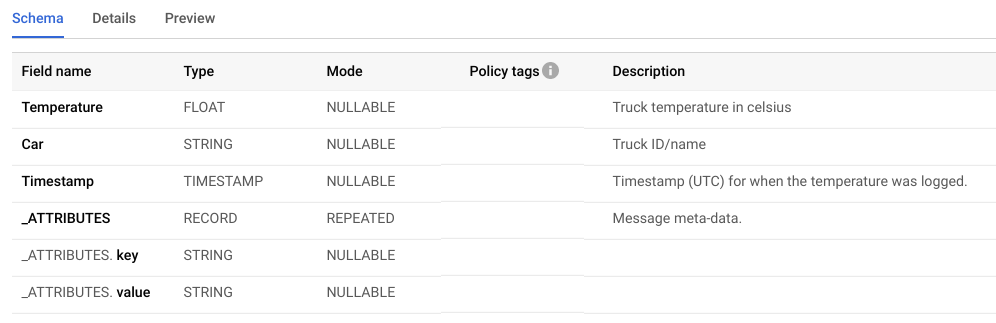

BigQuery schemas are usually represented as JSON and looks like below:

[

{

"description": "Truck temperature in celsius",

"mode": "NULLABLE",

"name": "Temperature",

"type": "FLOAT"

},

{

"description": "Truck ID/name",

"mode": "NULLABLE",

"name": "Car",

"type": "STRING"

},

{

"description": "Timestamp (UTC) for when the temperature was logged.",

"mode": "NULLABLE",

"name": "Timestamp",

"type": "TIMESTAMP"

},

{

"description": "Message meta-data.",

"fields": [

{

"description": "",

"mode": "NULLABLE",

"name": "key",

"type": "STRING"

},

{

"description": "",

"mode": "NULLABLE",

"name": "value",

"type": "STRING"

}

],

"mode": "REPEATED",

"name": "_ATTRIBUTES",

"type": "RECORD"

}

]

BigQuery performs best when your data is denormalized. Rather than preserving a relational (star or snowflake) schema you can improve performance by denormalizing your data with nested and repeated data structures. Nested and repeated fields can maintain relationships without the negative performance impact of preserving a relational (normalized) schema. The rationale is that the storage savings from using normalized data are less than the performance gains of using denormalized data. Joins require network communication (bandwidth) when shuffling while denormalization enable parallel execution.

Hence, we try to keep tables denormalized, mirroring the data objects we receive from our microservices. The truck temperature object above is a very simple example of a data object we have at MatHem, most objects (such as orders, subscriptions, products, members, etc.) contain more than 100 fields in a nested/repeated structure.

However, we don’t work with the JSON schema at all, instead we use the TableSchema class in the BigQuery API Client Library for Java in a small application named DataHem.Patcher.

2.2 DataHem.Patcher

DataHem.Patcher is a Java application that I developed to patch BigQuery table schemas from a descriptor file (see part 1 in this series of posts) stored in cloud storage. The application is invoked with a configuration as below:

{

"patches":[

{

"fileDescriptorBucket":"${_PROJECT_ID}-descriptor",

"fileDescriptorName":"${_FILE_DESCRIPTOR_NAME}",

"descriptorFullName":"${_DESCRIPTOR_FULL_NAME}",

"policyTagPattern":"${_POLICY_TAG_PATTERN}",

"tables":[

{

"tableReference":{

"projectId":"${_PROJECT_ID}",

"datasetId":"${_DATASET}",

"tableId":"${_TABLE}_staging"

},

"createDisposition":"CREATE_IF_NEEDED",

"timePartitioning":{

"field":null,

"requirePartitionFilter": true

},

"clustering":{

"fields":[]

}

}

]

}

The application loops through one or multiple patches and tables and support settings such as create disposition, time partitioning and clustering. The actual fields are described in the descriptor file under the specified descriptor name. The application checks if the current (old) table schema is equal to the “new” schema and if true then do nothing, if false then patch.

This post will be updated with links to both source code (it’s open source) and a dockerhub image.

The resulting BigQuery table schema looks like below:

In the next post (part 3) I will focus on the Dataflow pipeline and how we update it.